A large part of the curriculum for my first course in theology (taught by the ever-inspiring Dr. Cynthia Rigby) was theological vocabulary, and the process is just as you may recall from elementary school. We were given words each week which we had to define using dictionaries, lectures, and discussions; every few weeks there would be a short quiz where we were to prove our understanding of this new language we were discovering. We learned little words we thought we knew: Faith. Heresy. Grace. Vocation. Sin. Theology. We learned big words and phrases: Epistemology. Hermeneutics. Predestination. Homoousias/Homoiousios. Fides quaerens intellectum.

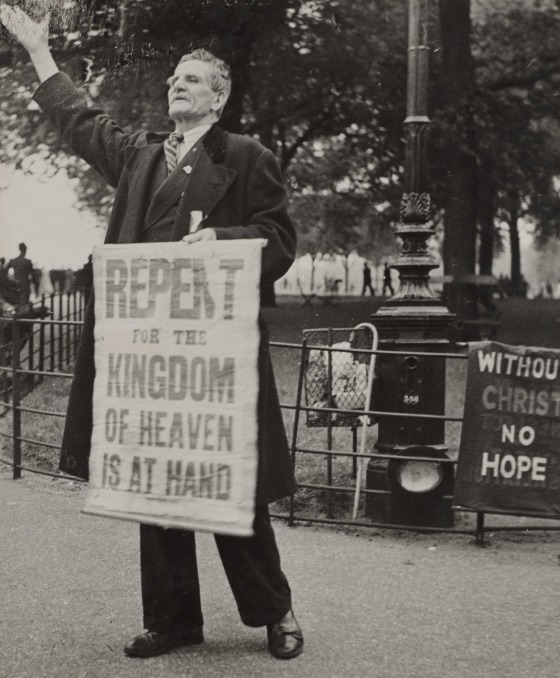

In the gospel reading this week (Luke 13:1-9) Jesus uses a word that a lot of us probably know, or at least think we know: repent. When I hear this word my mind is drawn to old-timey pastors holding signs on street corners that read “Repent for the kingdom is nigh!” (Matthew 3:2). I recall being a child, sitting in the old Mile High stadium in Denver, listening to Billy Graham declaring the sins of those in attendance and their need for repentance. Youth conference leaders begged us to come forward and repent of our sins so as to enter into relationship with God. In each of these cases, the definition of repentance has somehow been replaced with confession.

It’s understandable in the context in which I grew up, where salvific-evangelism and weekly reports of how many so-and-so had saved was king, but I sure wish they’d have just called it confession. I wish they called it for what it was: an act of acknowledging and articulating one’s sin.[1] Their altar calls rarely (if ever) allowed space or time for repentance; these moments in arenas and stadiums are momentarily life-changing, but what about tomorrow? What about when those who went forward to confess their sins had to go home and face the causes of their sins? What about those who confessed on Sunday morning then went about their life Sunday afternoon?

In our new testament scriptures, this word translated ‘repent’ comes from the Greek word μετάνοια (metanoia), and it essentially has two components to it: “sorrow for sin and turning from sinfulness to righteousness”[2] The Heidelberg Catechism – one of the documents the PC(USA) uses to help us understand our faith – tells us that in repentance there is “the dying-away of the old self, and the rising-to-life of the new.”[3] Going further, the catechism tells us that the dying-away of the old self persuades us “to be genuinely sorry for sin and more and more to hate and run away from it” and that, in rising-to-life of the new we have a “wholehearted joy in God through Christ and a love and delight to live according to the will of God by doing every kind of good work.”[4]

This is far beyond simply confessing of one’s sins; repentance is the confession of sin and the movement away from it, it’s admission and advancement. When, in the Lukan narrative, Christ tells those in his presence that they must repent, he’s not telling them to merely come forward, admit their sins, and then go on sinning again; no, he’s telling them to admit their sins and work to sin no more. He’s telling them that the mercy of God has afforded them this moment for repentance, for declaring one’s sins and a commitment to move away from them.

When we follow Christ’s call to repentance we take a long, hard look at our own life and the ways and means by which we have violated God’s will. We reflect on those deeds, thoughts, and words which have caused distance between us and our Creator. We admit where we have sinned, where we have failed, where we have done wrong and, in understanding repentance, we don’t stop there; we don’t admit our sins and then go on sinning – no, we confess where and how we have sinned and we work to remove ourselves from them. Repentance calls us to confession and change, to acknowledgement and advancement.

This repentance stuff isn’t just a personal-sin thing…it’s a Christian-community thing. We live in community and sometimes (quite often) we also sin in community. When we follow Christ’s call to repentance, we look at our Christian community’s complicity in slavery, not merely admitting complicity, but also making movements to ensure the end to slavery in all its forms.

We hold difficult conversations about systemic and institutional racism; we read books that don’t whitewash history but ones which plunge us into the blood and tears drawn by slave owners. We make conscious efforts and take deliberate actions to ensure equal and equitable opportunities for all people, not just in our Christian community but in our global community, calling out racism when we see it – even at the risk of our own security and safety.

When we follow Christ’s call to repentance, we confess the ways in which we have been hurtful, harmful, and hateful toward our LGBTQIA+ neighbors and siblings in Christ. But beyond confession we work to understand, love, encourage, and advance their rights and liberties. We meet to learn and understand language and the importance of word choice. We ensure our own companies – and those we support – refuse discrimination, bigotry, and prejudice. We listen to and honor the stories of coming out, of being invited in, of finding community, relationship, acceptance, and love. We follow Christ’s commands to “do to others as you would have them do to you”[5] and to “love your neighbor as yourself.”[6]

When we follow Christ’s call to repentance, we confess the ways in which we have ridiculed and refused, denied and derided, ignored and insulted those experiencing homelessness, those widows and orphans among us, those unjustly jailed and imprisoned, those who are beyond our income, our intelligence, our imagination. But beyond confession we stand against economic injustices which prevent financial proliferation and prosperity. We defund the ways and means of war, using the money instead to fund shelters and food banks, early childhood education and subsidized healthcare. We seek humane ways to enact justice, fair ways to shape reconciliation, and arrange for restoration. We give food and drink, shelter and clothing, health and healing as freely as it has been given to us.[7]

In repentance we not only confess our sins, we not only work to move away from them, but we live with “wholehearted joy in God through Christ and a love and delight to live according to the will of God by doing every kind of good work.”[8] Repentance isn’t some gloomy, dreary, downer – it’s a call to life abundant, life resplendent! Repentance gives us the opportunity to not only be renewed and restored, but to live into it. Through repentance we’re given a new life and a new way of living. Because of repentance we are able to invite others to join us in this joyful, delightful life.

Friends, Christ calls us to repent and he gives us opportunity upon opportunity to do so. But there will come a day…there will come a day when He will judge us. Christ will judge the ways in which we did or didn’t feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, and welcome the stranger. Christ will judge the ways in which we did or didn’t clothe the naked, care for the sick, and visit the imprisoned. Repent, my friends. Move away from the death of sin – “more and more…hate and run away”[9] from the old, dead life and run towards the life-giving, joy-filled life found through repentance with Christ. May it be so.

much love. sheth.

—–

[1] The Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms s.v. “confession”, Donald K. McKim (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2014), 63.

[2] The Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms s.v. “metanoia”, Donald K. McKim (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2014), 197.

[3] “The Heidelberg Catechism” Question 89 (4.089) from The Constitution of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A) Part I: Book of Confessions (Louisville: The Office of the General Assembly, 2016), 59.

[4] ibid.

[5] Luke 6:31

[6] Mark 12:31

[7] Luke 6:38

[8] “The Heidelberg Catechism” Question 90 (4.090) from The Constitution of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A) Part I: Book of Confessions (Louisville: The Office of the General Assembly, 2016), 59.

[9] “The Heidelberg Catechism” Question 89 (4.089), 59.